by: Rev. Dr. Roy Thomas

Respectfully and as a matter of conscience, I am writing to you about the renaming of Paul H. Cale Elementary School. In February of this year, when I learned that the school system’s original plan to employ a historian (to research the facts of this case) had been abandoned, I chose to do my own research. Following is my annotated paper, “Paul Cale and the Desegregation of Albemarle County Public Schools,” that presents the basic facts of Mr. Cale’s life, leadership, and legacy. If you GOOGLE “integration of Albemarle County Schools,” my research comes up first, because nothing else has been written on the subject.

Respectfully and as a matter of conscience, I am writing to you about the renaming of Paul H. Cale Elementary School. In February of this year, when I learned that the school system’s original plan to employ a historian (to research the facts of this case) had been abandoned, I chose to do my own research. Following is my annotated paper, “Paul Cale and the Desegregation of Albemarle County Public Schools,” that presents the basic facts of Mr. Cale’s life, leadership, and legacy. If you GOOGLE “integration of Albemarle County Schools,” my research comes up first, because nothing else has been written on the subject.

If the school’s name is changed, what will the children at Cale Elementary School be told? Mr. Cale did not support integration? Mr. Cale was responsible for delaying the desegregation of our schools? Mr. Cale did not embody our school values? Mr. Cale did not make significant contributions to our schools and world? He was “neither a hero nor a villain”? Nothing could be farther from the truth. The Advisory Committee found no evidence to support these statements. We now live in a culture of lies and defamation with no basis in fact. I pray we will not teach, model, or reinforce these unethical cultural norms for our children.

I hope you will read my research project. It contains copies of original primary sources about Mr. Cale. Note what African Americans who knew Mr. Cale said and wrote about him. I especially hope you will read the Virginia Gazette articles on Williamsburg-James City County Schools’ renaming of their elementary school that was named after their former Superintendent; it is the case I have found that is closest to the one the School Board is deliberating.

The public must know the whole truth about what Paul Cale did for students of all races and what he did to achieve full integration of Albemarle County public schools.

PAUL H. CALE AND THE DESEGREGATION OF ALBEMARLE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS

Rev. Dr. Roy S. Thomas, III

SEPTEMBER 26, 2019

In the multiplicity of news media reports about the renaming of the Paul H. Cale Elementary School, almost all reporters and individuals quoted have said that they did not know Mr. Cale.

I knew him intimately. I was his neighbor and friend; we shared many meals and fished together; several times I went with him to fish in the black waters of Chowan County, North Carolina, where he was raised; and I was Paul’s pastor from 1978 until his death in 1987.

To Paul, character was everything, and education was paramount. Throughout his 38 years as a teacher, coach, principal, and superintendent for Albemarle County Public Schools, he declared: “What you say teaches some, what you do teaches more, what you are teaches most.” He believed that character was the first prerequisite for a teacher.

First and foremost, Paul was an educator. His son and daughter were also teachers; two of his grandchildren are teachers; another grandchild is a principal. He served as president of the Virginia Association of School Administrators and as a member of the Committee on Raising the Level of Public Education in Virginia (whose final report about concrete ways to reduce the growing gap between the state’s best and worst public schools was called “a milestone in the history of Virginia’s public education”[i]).

Paul led Albemarle County’s public schools through consolidation, integration, and the implementation of expanded curricula, programs, and services. What he did for Albemarle County schools is undeniable. Under his leadership as Superintendent of Albemarle County Public Schools from 1947 to 1969:

- The 52 schools he inherited (44 had no central heat, 42 had no indoor plumbing; none had a cafeteria; only one had a library, only one had a science lab) were consolidated into 18 fully equipped modern buildings.[ii]

- The following schools were built: Albemarle, Burley, Brownsville, Henley, Jack Jouett, Murray, Rose Hill, Stone Robinson, Woodbrook, and Yancey.[iii]

- In 1969, Paul’s plan for a joint vocational technical education center–today’s Charlottesville Albemarle Technical Education Center (CATEC)–was approved by the school board.[iv]

- Paul led a segregated county school system to full integration without a single school closure or major incident.

In addition, the following programs and services were begun under Paul’s leadership:

- Special education[v]

- Driver training[vi]

- Free and reduced price lunches[vii]

- Guidance counselors and a school psychologist[viii]

- Head Start[ix]

- Libraries and librarians in every school[x]

- Vocational training[xi]

- Educational television (Albemarle was the first school system in Virginia to install a television translator)[xii]

- Foreign Exchange Student Program[xiii]

- Sex education[xiv]

- Night classes for adults[xv]

Paul led Albemarle County schools through the emotionally charged, crucial process of desegregation. He faced tremendous pressures to resist and prevent integration from the school board, the board of supervisors, prominent citizens, and parents. The Jefferson School African American Heritage Center’s publication, Pride Overcomes Prejudice, summarizes the situation: “In the county [of Albemarle] political leaders were almost unanimously behind resistance [to school integration] in any form…leadership was divided between massive resistance and local option segregationists.”[xvi] Speaking at the dedication of the new Burley High School [for Negroes] on April 8, 1952, John S. Battle (Virginia’s governor from 1950 to 1954) declared: “Segregation is a social arrangement for the betterment of relationships between different races living under a democracy as we see it.”[xvii]

Paul worked at the pleasure of and under the authority and supervision of the Albemarle County School Board and was required to carry out their policies and decisions, many of which promoted segregation. He had to navigate the troubled waters of lawsuits, state laws, and local ordinances and policies enacted against integration. For example:

- On May 19, 1954 (two days after the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision declaring school segregation illegal), the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors voted to continue operating a segregated school system.[xviii]

- On September 23, 1954, the Albemarle County School Board officially resolved that “the integration of white and colored students in the public schools…is against the best interests and contrary to the wishes of the great majority of both the white and colored races, and…the compulsory attendance law should be amended to exempt from its operation any child whose parent or legal guardian objects to integration.”[xix] Board member and University of Virginia professor, Dr. E. J. Oglesby, would later say, “The county will not build schools for integrated purposes. Negroes know whites will not operate integrated schools.”[xx]

- On April 14, 1955, the school board received formal communications from the parent teacher associations of McIntire and Meriwether Lewis schools stating they were “unalterably opposed to the integration of white and Negro children in Virginia’s schools.”[xxi]

- On June 23, 1955, the Virginia Board of Education announced its decision to “continue a policy of public school segregation throughout the state of Virginia.”[xxii]

- In the summer of 1956, the Virginia General Assembly passed Massive Resistance legislation to prevent school integration.[xxiii]

- In September of 1958, Governor J. Lindsay Almond Jr. closed Charlottesville’s Lane High School and Venable Elementary School to prevent their court-ordered desegregation. “This futile struggle split…into warring factions.”[xxiv]

- In 1959, the General Assembly passed new legislation authorizing the payment of tuition grants–popularly called “scholarships”–to children wishing to attend private schools (thereby circumventing integration).[xxv]

- In 1959, with the help of the state tuition grants, segregationists opened two private segregated schools in Charlottesville–Rock Hill Academy and Robert E. Lee Elementary School–for white students.[xxvi]

- In their 1962 budget, the Albemarle County School Board and Board of Supervisors included $125,000 for tuition grants that white children could use to attend a private school if their school was integrated.[xxvii]

- By 1965, the Albemarle County School Board had developed a “freedom of choice” policy (a form of “passive resistance to integration”) that allowed parents to choose the school their child attended.[xxviii] As Leon Dure, a retired southern newspaper editor living near Charlottesville, rationalized: “[We] do not feel the need for a law forbidding blacks and whites from association, but at the same time [we do]…not think governmental authority should be used to force interracial association.”[xxix]

In a 1956 article in Commentary, James Rorty wrote that integration plans for Albemarle County schools had moved forward more slowly than those in Norfolk schools. By 1955, Norfolk (where military installations were already legally integrated) had detailed plans for the admission of Negroes to white schools. Rorty reported that in his interview with Mr. Cale, Paul had explained that the practical realities of and widespread opposition to desegregation in Albemarle County had necessitated a slower pace.[xxx] Rorty’s paraphrases (presented as quotations in most media since October 2018) of Paul’s remarks are now being used to suggest that Paul H. Cale was a racist opposed to integration and thereby unworthy of having his name on a school. However, quite the opposite is true. Paul was not opposed to integration. He understood that in order to keep schools open during the extended battles over desegregation, integration had to move along a continuum of building trust among the factions (while waiting for more than a decade of lawsuits to be adjudicated in the courts).

Consider what was happening in central Virginia and throughout the Commonwealth (that is, the formidable realities Paul was facing) when Mr. Rorty interviewed Superintendent Cale:

- On January 9, 1956, Virginians voted 304,154 to 146,164 in a statewide referendum to call for a constitutional convention to amend the Commonwealth’s constitution to allow tuition grants to be paid by the state to private schools on behalf of children who refused to attend an integrated school.[xxxi]

- On March 5, 1956, a constitutional convention of 40 delegates met in Richmond and unanimously amended Section 141 of the state constitution to legalize tuition grants to pupils attending private schools.[xxxii]

- In July 1956, a mass meeting was held at Lane High School, attended by a reported 1,200 persons, to demonstrate their opposition to desegregation. Petitions opposing desegregation, signed by 8,736 people, were presented at this rally.[xxxiii]

- In a special session of the Virginia legislature that began August 27, 1956, the forces of Harry F. Byrd passed Massive Resistance legislation that (1) created a state School Placement Board with the authority to handle all Virginia pupils’ school assignments and requests for transfers (thus, stripping the superintendent of his power to transfer students and integrate schools); (2) required the governor to close any school facing court-ordered integration; (3) cut off all state funds from any school district with an integrated school; (4) authorized the state to provide private-school tuition grants from public funds to parents in any district where the public schools were closed to prevent desegregation; and (5) placed legal restrictions on the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and created two joint committees to investigate the NAACP, which had been filing desegregation lawsuits in Virginia.[xxxiv]

Now ponder Paul H. Cale’s actions and decisions on racial justice and desegregation during his years of service as Superintendent of Albemarle County Public Schools 1947-1969:

- The Norfolk School Board offered Paul their superintendent’s job (with a 20% increase in salary) which he declined. They would not have offered him this position if he had been a racist opposed to integration. Mr. Cale’s son, Paul H. Cale Jr., believes that his father felt that it was not right for him to leave Albemarle schools at this critical time of desegregation and dissension.[xxxv]

- From the beginning, Paul prioritized addressing the inadequate facilities and programs in the Negro schools. In his first school board meeting as superintendent in June 1947, he presented the deplorable condition of the Free Union colored school and asked permission to close the school and transfer the students. The board granted his request on the condition that the superintendent could “secure a station wagon or some other suitable means of transporting the approximate twelve students to the White Hall School.”[xxxvi] Two months later, the school board authorized the superintendent to have running water put in the Crozet Negro school.[xxxvii]

- Cale’s first major school improvement project was the construction of Burley High School. In his second month as superintendent (seven years before Brown v. Board of Education), the school board authorized negotiations to purchase land for a Negro high school in the Rose Hill district.[xxxviii] In his article, Mr. Rorty admits: “In 1950, four years before the Supreme Court decision, Albemarle County had built a comprehensive high school for Negroes which had cost more per pupil than the white high school, and the county’s future building program embodied genuine equality for white and colored.”[xxxix]

- In the 1951-52 school year, a training program for licensed practical nurses was begun at the new Burley High School (two years before it was implemented for white high school students).[xl] It allowed scores of African American women (and some men) to become credentialed nurses and work in hospitals that had been largely segregated.[xli]

- After the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Paul led the school board to establish a Citizens Advisory Committee composed of black and white members chosen by the parent teacher associations of all schools, Negro and white.[xlii] Compare this to Virginia Governor Thomas E. Stanley’s decision to appoint an all-white, all-male state commission to address desegregation.[xliii]

- Lydia Hailstork, an African American teacher at Burley prior to desegregation, recalls: “The county began integrated teachers meetings early, I mean before integration came. We began to meet with the White teachers, with the staff.”[xliv]

- Based on recommendations from “Negro leadership in the school system [when the integration of county schools began, Mr. Cale]…got the principals at the schools to set the tone to be color blind, to treat everybody as individuals.”[xlv]

- When the court ruled that Albemarle schools would have to be integrated in 1963, the school board banned all dances, parties, clubs, sports, and other extracurricular activities that would involve social contacts between black and white students.[xlvi] The chairman declared that the ban’s “enforcement would continue to keep down the number of Negro applicants through the years to come.”[xlvii] Paul stood firmly opposed to this policy.[xlviii] The Board of Supervisors eventually fired members of the school board, and the ban on sports and clubs was never implemented.[xlix]

- When Burley High School closed and all the students were transferred to Albemarle High School, Paul brought Zelda Murray, the respected African American secretary at Burley, to Albemarle High’s front desk so that she would be the first person the Burley students saw when they entered their new school.[l]

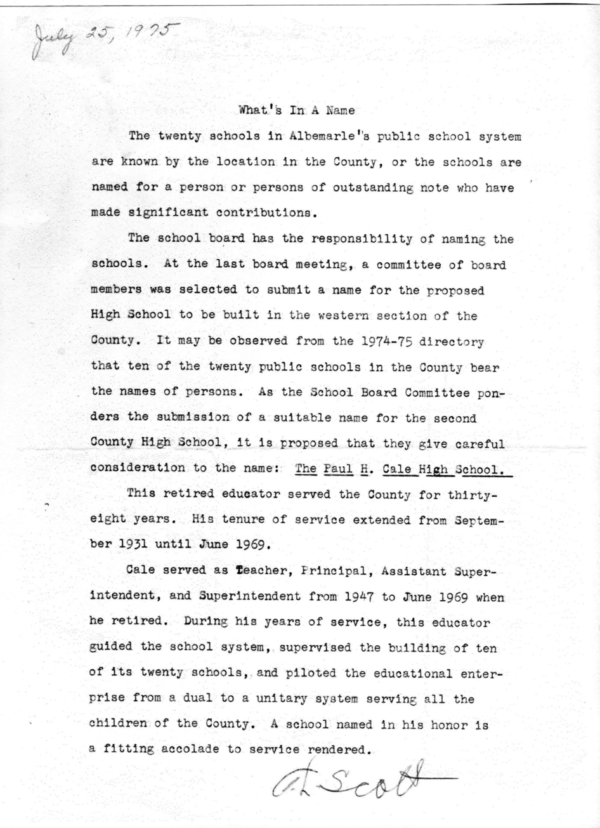

- Cale hired A. L. Scott, Burley’s last principal, as his Assistant Superintendent of Instruction.[li]

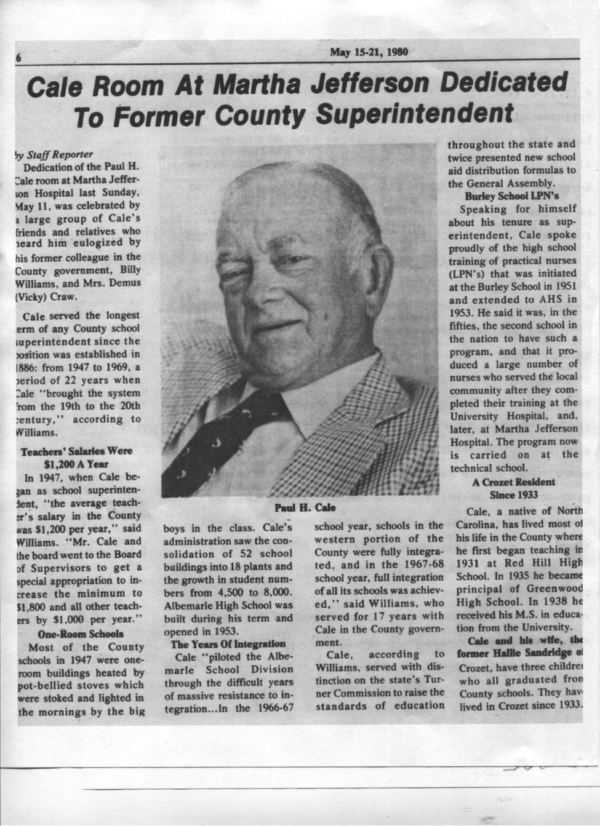

- Scott, an African American, wrote a letter [see attached copy of the July 25, 1975 letter] to the school board in which he stated: “This educator [Mr. Cale]…supervised the building of ten of its twenty schools, and piloted the educational enterprise from a dual to a unitary [integrated] system serving all the children of the County. A school named in his honor is a fitting accolade to service rendered.”[lii]

- Paul supported the efforts of Crozet Baptist Church (where I was pastor 1978-2005) to build relationships with black churches and the African American community. At special integrated worship services (rare in those days) that we sponsored, a number of African Americans would come over and greet Mr. Cale. They loved and respected him for what he had done for black and white children (and adults) in Albemarle County.

- One’s descendants can reflect an individual’s real character and influence. Paul’s grandchild is married to an African American. Another grandchild is principal of a Northern Virginia school with 43 nationalities in the student body.

Paul’s teachers knew his leadership and character best. In their bicentennial book, Development of Public Schools in Albemarle County from the late 1700’s to 1976, the integrated Retired Teachers’ Association of the County of Albemarle remembered their superintendent this way: “He transformed a scattering of single teacher schools into…larger, more modern facilities…an educational system for today. He piloted the schools through the stormy history of the period of school desegregation.”[liii]

The Paul Cale I knew was no racist. He built relationships and trust within the white and black communities and mediated between the “massive resisters” and vocal black leaders to keep Albemarle County’s schools open when other schools were closed. He did not retire until the school system was fully integrated.

Paul’s primary commitment was to the needs, best interests, and quality education of his students. “He worked long hours to the detriment of his health in order to better the lives of everyone in his sphere.”[liv] It was his goal each year to visit every classroom in every school and give attention to children with special needs. He believed that “we are all God’s children.”

When he retired, The Daily Progress editor wrote: “Mr. Cale somewhere found the time to improve the instruction, to widen the curriculum, and to turn out students above the average academically and good citizens as well. In addition, he handled with skill, tact and unending patience, the trying times of desegregation and then the federally-enforced integration of Albemarle schools…the county was also fortunate to have had so dedicated and competent a leader during a period of such stern challenge to public school superintendents throughout the South.”[lv]

The battle over desegregation was a (un)holy war. Segregationists believed that the mixing of the races violated the divine design. Integrationists and the courts demanded immediate desegregation. Superintendent Cale stood in the divide between the INTEGRATION NEVER and INTEGRATION NOW camps. He built relationships with both sides and led Albemarle County public schools to full integration without a single school closure or major incident.

In 2016 Williamsburg-James City County Public Schools renamed Rawls Byrd Elementary School that had been named after their long-time superintendent. Rawls Byrd was a vocal segregationist.[lvi] He said that he would “shut down the school before [he] saw a Negro attend a white school in Williamsburg-James City County.”[lvii] Rawls Byrd visited the all-black faculty meeting at the African American Bruton Heights School and told them that if one of their students kept trying to attend one of the WJCC white schools, he would shut down Bruton Heights and fire all the teachers. He refused to shake hands with black students graduating from Bruton Heights. He told one African American student applying to a white school that if he did not rescind his request, he would never graduate and that his father would never find work in town again.[lviii]

Paul Cale was no Rawls Byrd. He was not a segregationist. He treated all students and staff with respect, and they respected him. Rawls Byrd had said that he would retire if his schools were ever forced to integrate, and he did. Mr. Cale led Albemarle schools through the stressful battles and realities of desegregation until they were finally and fully integrated–and remained as superintendent for two additional years.

Rosa Belle Moon Lee was a beloved African American teacher in Albemarle schools for many years. Her husband, Otis Lee, was the first principal of Murray Elementary School and later worked with Paul in the ACPS central office. The Lee family so respected Paul that in Mrs. Lee’s obituary they included the fact that it was Mr. Cale who had hired her–first to teach at the all black Yancey Elementary School and then to teach at the integrated Stone Robinson Elementary School after Albemarle County began desegregating the public schools.[lix] Prior to being hired by Mr. Cale, Mrs. Lee had held a school cafeteria job in Richmond, Virginia.

Also in 2016, Henrico County Public Schools renamed Harry F. Byrd Middle School that had been named after the former Virginia governor and United States senator who spearheaded the Massive Resistance movement against the integration of public schools.[lx] Byrd co-authored and engineered the Southern Manifesto, signed by 110 southern United States congressmen, promising to resist school integration “by all legal means” and pledging that the South would follow a policy of “massive resistance” to Brown. Harry Flood Byrd and his forces were primarily responsible for the Massive Resistance legislation passed by the Virginia legislature to maintain segregation in Virginia.[lxi]

Paul Cale was no Harry Byrd. He fought to keep schools open, not close them! Paul was not a racist. He did not lead Massive Resistance against desegregation. He led Albemarle schools through Massive Resistance to full integration.

In the late 1960’s, Curtis Tomlin was part of a group seeking to revive Crozet Park. He recalls, “As a group, we agreed to seek community-wide support and funding, and each of us took a group of names to contact for that purpose. One of the names I selected, on purpose, was that of Mr. Paul H. Cale. I called for an appointment and was graciously invited into his home on St. George Ave. Mr. Cale brought out his checkbook and while writing a check, he asked me if we intended to keep the park open to everyone, including the black community. My reply, simply, was ‘We had not thought not to!’ He smiled, thanked me and said, ‘That’s what I wanted to hear.'”[lxii] [see attached copy of his January 3, 2019 letter to the Crozet Gazette]

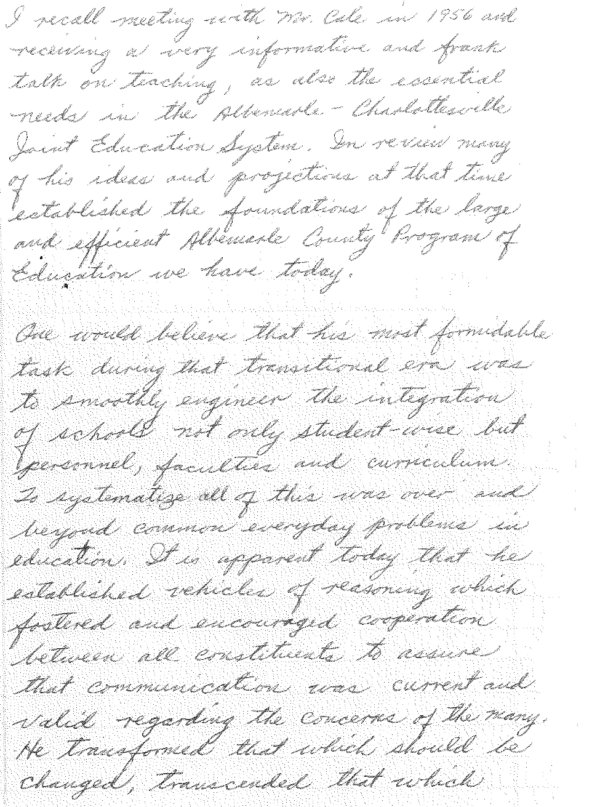

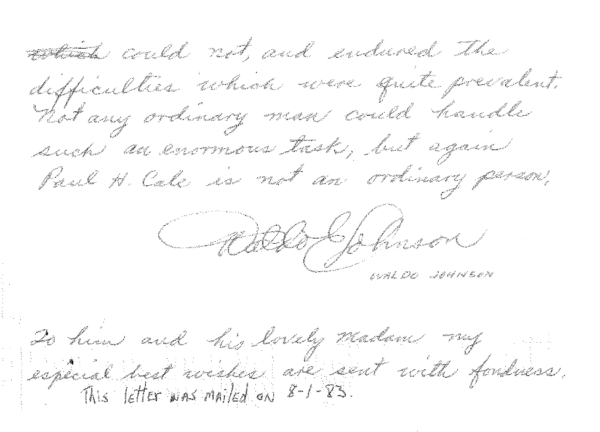

Waldo Johnson was an African American veteran of World War II. He taught art at segregated Burley High School and late at integrated Albemarle High School. He sent Paul and Hallie Cale a golden wedding anniversary card. Inside the card was a handwritten letter [see attached August 1, 1983 letter]. Mr. Johnson wrote, “One would believe that his [Paul’s] most formidable task during that transitional era was to smoothly engineer the integration of schools…It is apparent today that he established vehicles of reasoning which fostered and encouraged cooperation between all constituents…He transformed that which should be changed, transcended that which could not, and endured the difficulties which were quite prevalent. Not any ordinary man could handle such an enormous task, but again Paul H. Cale is not an ordinary person.”[lxiii]

Paul was one of the most widely respected and beloved persons I have ever known. I believe that Paul H. Cale is a most appropriate name for one of the county’s most diverse schools. The mission of Albemarle County schools is “to establish a community of learners and learning, through relationships, relevance and rigor, one student at a time.” Mr. Cale carried out that mission as a teacher, coach, principal, and superintendent in the Albemarle school system for 38 years. The core values of Albemarle schools are excellence, young people, community, and respect. Paul Cale embodied those values until his death. I was with him the day he died.

In 2017 the Albemarle High School Alumni Association (with 4,474 members) inducted Paul H. Cale into the Albemarle High School Alumni Hall of Fame. They celebrated that Mr. Cale was able to secure a federal grant to fund resources and treatment for students with impaired speech and hearing, that he greatly expanded curriculum (the number of courses offered in Albemarle County public schools tripled under his tenure as Superintendent), and that with skill, tact, and patience Mr. Cale influenced many to change their hateful, racist attitudes! [You can watch the induction ceremony online (Go to minute 57:00) at http://www.albemarlealumni.com/A-Night-To-Remember-2017.htm].

These are people who knew the REAL Paul Cale–his life, leadership, and legacy. After 500+ hours of research, I have concluded that Paul Cale did more for Albemarle County schools and students of all races than any other human being.

Roy Thomas’ Address to Cale Elementary School Renaming Advisory Committee

July 30, 2019

The news release of the 1956 Commentary article (implicating Paul Cale as a racist) catapulted me into a state of shock and disbelief. It was so unlike the Paul Cale I knew. I was his pastor, neighbor, and friend for nine years.

In February, when I learned that the school system had dropped its plan to hire an historian to research the issues raised in the article, I decided to do my own research. The Cale family did not ask me to do this; they didn’t even know I was doing it until I contacted them to clarify some information.

In 1956 James Rorty came to Virginia to assess why the 1954 Supreme Court order to desegregate public schools was not moving forward in the South. After an interview with the Superintendent, he wrote that Mr. Cale gave specific reasons[i] why desegregation was not practicable in 1956:

- First, Paul said that desegregation in Virginia could lead to the closing of public schools.[ii] Indeed, this did happen all across Virginia. My Lane High School (housed in this building we’re meeting in tonight) is a prime example. Prince Edward County public schools were closed for five years.[iii] “The prevailing public mood at this time was to close public schools rather than to permit any [racial] mixing whatsoever.”[iv]

- Second, Paul said that the busing of Negro students with white students could create dangerous conflicts.[v] Indeed, tensions were running so high then that this was a very real possibility. I remember being accosted on the front lawn of this building by two Burley High School football players who had transferred to Lane, and to this day I thank God it became only a verbal attack. This incident (that occurred nearly a decade after the interview) scared me to death. I can only imagine the abuse that African American students suffered during the years of desegregation.

- Third, Paul told Rorty that if schools were integrated, white parents would not permit their children to be taught by inferior Negro teachers.[vi] Well, when integration began here in central Virginia, the parents of some 700 children did not allow them to be taught by Negro teachers and enrolled them in Rock Hill Academy and Robert E. Lee Elementary School, Charlottesville’s new private segregated schools.[vii] Black teachers were perceived as inferior by many white people. It is also true that African American teachers did not have the access to higher education that white teachers did then–due to SEGREGATION! Tonight I can assure you that Paul Cale did not believe that African American teachers were inferior to Caucasian teachers in their personhood or ability to teach.

The Paul Cale I knew was no racist or segregationist. In my research I found no evidence that Paul Cale opposed desegregation or tried to do anything to prevent the integration of public schools. To the contrary, I found concrete evidence that Paul supported integration:

- After the Supreme Court desegregation decision, he formed an integrated Citizens Advisory Committee composed of representatives chosen by the PTA’s of all schools, black and white.[viii] Virginia’s governor, on the other hand, enlisted an all white male commission.[ix]

- Paul instituted integrated teachers meetings long before the School Board authorized integration of the schools.[x]

- He opposed the School Board’s 1962 ban on sports and social activities if a school was forced to integrate.[xi]

- He hired the first African Americans to fill leadership positions in the central office– Otis Lee and A. L. Scott, Burley High School’s last principal who became assistant superintendent of instruction.[xii]

- He opposed segregation at the Crozet Park.[xiii]

- He supported integrated services and programs at his church.[xiv]

I especially want to emphasize the Licensed Practical Nurse diploma program at Burley High School that began under Paul’s leadership in 1951 (two years before the program was offered at a white high school).[xv] The UVA School of Nursing was segregated at the time, but this joint program between Burley and UVA allowed black students to become credentialed nurses[xvi] (even though the University never allowed them inside the nursing school and never acknowledged them as UVA alumni). Students took basic nursing classes their senior year and then completed practical training at the then segregated UVA Hospital. The graduates were among the first black nurses at the hospital, working first as “hidden nurses” in segregated wards in the dank basement.[xvii] The integration of UVA Hospital did not begin until 1960 after a lawsuit, filed by black employees, demanded desegregation and better working conditions.[xviii] This is direct evidence that as early as 1951, Paul Cale was acting to promote integration in central Virginia. This was three years before Brown v Board of Education. It would be 1970 (nearly two decades later) before the first black nurse graduated from the UVA School of Nursing.[xix]

I have heard two concerns some have raised about Mr. Cale. One is that some African Americans heard him use the word “Negra.” “Negra” is not the “N” word. It is how people raised in eastern North Carolina (like Paul Cale) and in Southside Virginia (like my mother) pronounced the word “Negro” in the first half of the 20th century. My mother never said “tomato”; she called the vegetable “tomata.” It’s what she heard and learned growing up. She didn’t say “Negro”; she said “Negra.” I can assure you it was NOT the “N” word. I am glad that I learned early on that this term was offensive to African Americans.

The bigger concern raised about Mr. Cale has been why it took so long to fully integrate Albemarle County public schools–13 years after Brown v. Board of Education to be exact. This is a legitimate question, so I have been researching it for some weeks now. Here is what I have found:

- For nearly five years after the Supreme Court decision, NO school in Virginia was integrated because of the 1956 Massive Resistance legislation passed by the General Assembly which gave Virginia’s governor the authority to shut down any school that was forced to desegregate.[xx] On September 4, 1958, Virginia Governor, J. Lindsay Almond Jr., divested superintendents of Virginia schools of their authority to desegregate their schools.[xxi] In addition, the new state Pupil Placement Board (that assumed the superintendents’ responsibility to assign students) blocked the assignment of black students to white schools.[xxii] The Northerner James Rorty simply did not understand the intensity and intractability of racism and segregation in the South. In his 1956 article, he wrote, “Virginia has gained at most a year of grace before desegregation begins.”[xxiii] Well, it was 1959 before a single Negro student entered a white school in this state for the first time.[xxiv]

- From 1959 to 1963 the racist, segregationist School Board made sure that there was no integration of Albemarle County schools. Dr. E. J. Oglesby was the Board chairman from 1960 to 1963. In a 1958 article in The Nation magazine, Oglesby declared: “We’ve got enough money here…to operate private schools for the whites. What the niggers are gonna do, I don’t know. If we have to close the schools, of course, the nigger’ll have to suffer from it…Then, if the federal government says we have to operate…integrated schools, we’ll be ready to get out the bayonets. There were more Yankees killed in the last one [war] than Southerners, and if they want to try it again, let ’em come on down.”[xxv] Yes, this UVA professor was the Albemarle County School Board chair from 1960 to 1963. He was also a member of the state Pupil Placement Board for six years![xxvi] “It was not until 1963 that the Virginia Pupil Placement Board–under judicial pressure–assigned white children to formerly black schools for the first time.”[xxvii]

- In the summer of 1963, the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors removed the four racist members of the school board who were leading the local fight against desegregation.[xxviii] That fall black students enrolled in the Albemarle County’s public schools for the first time.[xxix] The newly formed school board rescinded the 1962 ban on sports and social activities at integrated schools.[xxx] Furthermore, they did not fire Mr. Cale because (1) he opposed the school ban[xxxi] and (2) he was not a racist or segregationist.

- Over the next three years the new school board approved, designed, funded, and built Henley Junior High School and Jack Jouett Junior High School, which had to be completed before all Burley High School students could be transferred to Albemarle High School.[xxxii] In addition, Brownsville Elementary and Woodbrook Elementary schools were built to address overcrowding, desegregation, and growth.[xxxiii] The county school system was fully integrated in 1967[xxxiv], which was the first year that UVA hired an African American professor.[xxxv] It would be 1972 (five years after the integration of Albemarle County schools) before the University of Virginia was fully integrated without quotas.[xxxvi]

- I know this seems agonizingly slow–and it was! In the spring of 1968 (one year after Albemarle schools were fully integrated), the U.S. Department of Health. Education, and Welfare estimated that “only 14 percent of the black pupils in the eleven former states of the Confederacy attended desegregated schools.”[xxxvii]

I believe Paul H. Cale is the RIGHT NAME for one of our most diverse schools, because he has done more for Albemarle County schools and students of all races than any other human being:

- He led the consolidation of 52 schools and oversaw the construction of ten of today’s schools..

- He led a completely segregated school system to full integration without a single school closure or major incident.

- Under his leadership: Head Start, special education, free lunches, vocational training, sex education, the foreign exchange student program, educational television, school libraries and librarians, guidance counselors and school psychologists had their beginnings in the Albemarle County school system.

- And in 1969, his last year as Superintendent, the School Board approved his final vision for a joint vocational technical education center–today’s CATEC.

The mission of Albemarle County schools is “to establish a community of learners and learning, through relationships, relevance and rigor, one student at a time.” Mr. Cale carried out that mission as a teacher, coach, principal, and superintendent for Albemarle County public schools for 38 years. The core values of Albemarle schools are excellence, young people, community, and respect. The Paul Cale I knew embodied those values until his death.

I close with four concerns that I have: (1) Since the October news release, it has appeared to me that many have presumed Paul Cale guilty until proven innocent, which is incompatible with America’s view of justice. (2) Some have suggested that the name of the school should be a separate issue from the person himself. This is impossible because the current name is a person and represents his values, leadership, service, and everything he did for Albemarle County schools. (3) My sincere hope is that your final decision will not be based on a false narrative or the loudest voices or personal agendas.

(4) My biggest fear is that Paul Cale will become a scapegoat and sacrificial lamb for collective guilt or a particular cause.

ROY THOMAS’ ADDRESS TO THE ALBEMARLE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD

September 26, 2019

I oppose the recommendation to rename Paul H. Cale Elementary School for FOUR REASONS:

No. 1: The Advisory Committee based their recommendation to rename the school on FALSE INFORMATION and ABSENCE OF EVIDENCE. Their report states: The continued segregation of county schools long…after Charlottesville City’s integration of schools made the continued use of the name of Cale Elementary School CONTROVERSIAL. The truth is: Neither school system was fully integrated until 1967. The Albemarle County Public Schools website (under “History of Burley Middle School”) reads: “In June 1967, Burley ceased being an all black high school for city and county students.” This invalidates the Committee’s rationale.

Their report also says: Nor did we find any indication that…[Mr. Cale] ever pushed to have integration occur faster…this made the continued use of the name of Cale Elementary School CONTROVERSIAL. The truth is: In 1958 Governor Lindsay Almond stripped Virginia school superintendents of their ability to integrate their schools and gave sole authority for transferring students in all public schools to the racist Virginia Pupil Placement Board (that did not assign a black student to a white school until 1963 under judicial pressure.). The Advisory Committee chair said, Somebody had to have their foot on the brake. They did–Virginia’s Governor and Pupil Placement Board! This invalidates the Committee’s rationale.

The Advisory Committee based their decision largely on what Mr. Cale didn’t say or didn’t do–evidence that would not stand up in any court. The truth is: The Committee found NO evidence that Mr. Cale said or did anything to OPPOSE or DELAY integration.

No. 2: The Advisory Committee failed to base their recommendation on the facts of all that Paul DID DO to achieve integration in a society dead set against it:

- After the 1954 Supreme Court decision declaring segregation illegal, Paul formed an integrated Citizens Advisory Committee. Virginia’s Governor appointed an all-white male commission!

- Paul instituted integrated teachers meetings long before the School Board (and courts) authorized integration of the schools.

- Paul hired the first African Americans to fill leadership positions in the school system’s central office.

- Paul opposed segregation at Crozet Park.

- In 1951, Paul oversaw the development of a Licensed Practical Nurse diploma program at the new Burley High School, which allowed black students to become credentialed nurses. The Burley graduates were among the first black nurses at UVA Hospital. It was 1970 (19 years later) before the first black nurse graduated from the UVA School of Nursing. This is direct evidence that eight years before a Negro student enrolled in a white school in Virginia, Paul was acting to achieve integration in central Virginia.

- Paul led a completely segregated school system to full integration without a single school closure or disruption of the education of students (which did happen in Charlottesville).

No. 3: The Advisory Committee and the MEDIA concluded that a 1956 Commentary magazine article depicted Paul Cale as a racist who questioned and opposed integration when, in fact, what Paul said in the article was that integration was NOT “PRACTICABLE” in 1956:

- Because “integration would generate dangerous conflicts.” It did!

- Because “if integration were to be enforced…it would be necessary to close… schools.” Indeed, school closures did occur all across Virginia, including Venable and Lane in our city, and

- Because “white parents would not permit their children to receive instruction from inferior Negro teachers.” When integration began, the parents of 700 white children did NOT allow their children to be taught by black teachers and enrolled their kids in the two new segregated schools in Charlottesville. Also, Negro teachers did NOT have the access to higher education that white teachers did then–because of SEGREGATION. I can assure you that the Paul Cale I knew did NOT believe in the innate inferiority of African American teachers. DON’T JUDGE A MAN BY QUESTIONABLE PARAPHRASES IN A MAGAZINE ARTICLE WRITTEN 63 YEARS AGO! JUDGE A MAN BY HIS LIFE AND ACTIONS.

No. 4: The Advisory Committee and THE MEDIA failed to acknowledge and publish everything that Paul Cale DID for Albemarle County Public Schools and for the education and betterment of students of all races:

- Paul led the consolidation of 52 substandard schools and oversaw the construction of ten of today’s schools.

- Under his leadership Head Start, special education, free lunches, vocational training, sex education, the foreign exchange student program, school libraries and librarians, guidance counselors and school psychologists had their beginnings in Albemarle County.

- Under his leadership Albemarle was the first school system in Virginia to introduce educational television in classrooms.

- Paul was a member of the Committee on Raising the Level of Public Education in Virginia, whose final report about concrete ways to reduce the growing gap between the state’s best and worst public schools was called “a milestone in the history of Virginia’s public education.”

- The Licensed Practical Nurse training program at Burley was one of the first in the state and in the NATION.

The new Albemarle County Schools RENAMING POLICY states: “The committee shall examine whether the individual has made outstanding contributions of state, national or worldwide significance in light of the Board’s adopted vision, mission and goals.” Paul Cale DID THIS, and this should be and IS the ONLY criterion for the School Board’s upcoming final decision on renaming. TO CHANGE THE NAME OF CALE SCHOOL would be a GRAVE INJUSTICE perpetuating the growing culture of defamation and untruth in our country.

Two years ago the Albemarle High School Alumni Association (with over 4,000 members) inducted Paul H. Cale into the AHS Hall of Fame, citing how he influenced many to change their hateful, racist attitudes. [You can watch the induction ceremony at (Go to minute 57:00) http://www.albemarlealumni.com/A-Night-To-Remember-2017.htm]. These are the people who knew the REAL Paul Cale–his life, leadership, and legacy. Paul Cale is NOT a symbol of racism; he didn’t have a racist bone in his body! His name is NOT “controversial” except in the minds of some people who never knew him. I hope you will vote to keep the NAME the SAME, because Paul Cale has done more for Albemarle County schools and students of all races than any other human being. Thank you.

Epilogue

I am a Charlottesville native and a graduate of the University of Virginia. I was a student in Charlottesville public schools from 1955 to 1967 (the desegregation era I have been describing in this treatise) and am now a resident of Albemarle County. From 1978 to 2005, I was the pastor of Crozet Baptist Church. I was Paul Cale’s minister for nine years.

My motivation to begin this research was to defend the good name of Paul H. Cale (or to discover if he was someone other than the person I knew). In February of this year, I learned that Albemarle County Public Schools’ plan to hire an historian to research the Cale/desegregation years had been abandoned.[i] Since then, I have devoted myself tirelessly to doing this research myself and now present to you my findings and interpretations.

Know that I support the new school naming policy and the work of the name review committee. I will also support the final decision on the renaming of Cale Elementary. I just hope it will not be based on a false narrative. Personally, I oppose all forms of racism and social injustice–interpersonal, legal, structural, and systemic. The Paul Cale I knew did too.

Albemarle County lies in the shadow of the capitol of the Confederacy. We still live with the emotive, racist scars of slavery, Civil War, Jim Crow, desegregation, and August 11-12, 2017 in Charlottesville, et cetera. The year 2019 marks the 400th anniversary of the first slave ship’s arrival at Jamestown in August 1619. We ignore this traumatic event at our own peril. As W.E.B. Dubois wrote in his 1903 work, The Souls of Black Folk, “The nation has not yet found peace from its sins; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people.”[ii]

Endnotes

[i] The Daily Progress, April 30, 1967.

[ii] The Daily Progress, October 16, 1968.

[iii] Development of Public Schools in Albemarle County from the Late 1700’s to 1976: A Bicentennial Project of the Retired Teachers Association of the County of Albemarle, 1976.

[iv]Albemarle County School Board Minutes, January 13, 1969, and August 11, 1969.

[v] Ibid., December 14, 1967.

[vi] Ibid., August 13, 1953.

[vii] Ibid., February 17, 1969.

[viii] Ibid., December 14, 1967, and Joint Committee for the Control of the Jackson P. Burley High School Minute Book No. 3, March 8, 1962 and May 8, 1962.

[ix] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, March 10, 1966.

[x] Lee, Otis. A History of Public Instruction in Albemarle County, Virginia, p. 24.

[xi] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, May 13, 1952.

[xii] Ibid., December 14, 1967.

[xiii] Ibid., September 16, 1963.

[xiv] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, May 13, 1965, and Joint Committee for the Control of the Jackson P. Burley High School Minute Book No. 3, June 15, 1965.

[xv] Joint Committee for the Control of the Jackson P. Burley High School Minute Book No. 1, December 6, 1955.

[xvi] Gaston, Paul M., “1955-1962 Public School Desegregation: Charlottesville, Virginia,” Pride Overcomes Prejudice: A History of Charlottesville’s African American School, Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, p. 96.

[xvii] Joint Committee for the Control of the Jackson P. Burley High School Minute Book No. 1, April 8, 1952.

[xviii] Albemarle County Board of Supervisors Minutes, May 19, 1954.

[xix] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, September 22, 1954.

[xx] Crowe, Dallas R. Desegregation of Charlottesville, Virginia Public Schools, 1954-1969: A Case Study, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1971, p. 80.

[xxi] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, April 14, 1955.

[xxii] Bryant, Florence C. One Story About School Desegregation, p. 18.

[xxiii] Thorndike, Joseph J. “The Sometimes Sordid Level of Race and Segregation: James J. Kilpatrick and the Virginia Campaign against Brown,” The Moderates’ Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 1998, p. 63.

[xxiv] Moore, John Hammond, Albemarle: Jefferson’s County 1727-1976, Albemarle County Historical Society, 1976,

- 435.

[xxv] Lewis, Andrew B. “Emergency Mothers: Basement Schools and the Preservation of Public Education in Charlottesville,” The Moderates’ Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 1998, p. 98.

[xxvi] Moore, John Hammond. Albemarle: Jefferson’s County 1727-1976, Albemarle County Historical Society, 1976,

- 436.

[xxvii] Albemarle County Board of Supervisors Minutes, May 2, 1962.

[xxviii] Daugherity, Brian J. Keep on Keeping On: The NAACP and the Implementation of Brown v. Board of Education in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2016, p. 118.

[xxix] Hershman, James J., Jr. “Massive Resistance Meets Its Match: The Emergence of a Pro-Public School Majority,” The Moderates’ Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 1998, p. 133.

[xxx] Rorty, James. “Virginia’s Creeping Desegregation: Force of the Inevitable,” Commentary, 1956, p. 51.

[xxxi] Holton, Linwood. “A Former Governor’s Reflections on Massive Resistance in Virginia,” Washington and Lee Law Review, Volume 49, Issue 1 (1992). p. 18.

[xxxii] Pratt, Robert A. The Color of Their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond, Virginia 1954-89, University Press of Virginia, p. 6.

[xxxiii] Crowe, Dallas R. Desegregation of Charlottesville, Virginia Public Schools, 1954-1969: A Case Study, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, 1971, p. 53.

[xxxiv] Pratt, Robert A. The Color of Their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond, Virginia 1954-89, University Press of Virginia, pp. 6-7.

[xxxv] Letter written by Paul H. Cale Jr., December 7, 2018.

[xxxvi] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, June 12, 1947.

[xxxvii] Ibid., August 14, 1947.

[xxxviii] Ibid., July 22, 1947.

[xxxix] Rorty, James. “Virginia’s Creeping Desegregation: Force of the Inevitable,” Commentary, 1956, p. 51.

[xl] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, May 12, 1949 and April 10, 1952, and Joint Committee for the Control of the Jackson P. Burley High School Minute Book No. 1, May 6, 1952.

[xli] The Daily Progress, March 30, 2019.

[xlii] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, March 16, 1955.

[xliii] Rorty, James. “Virginia’s Creeping Desegregation: Force of the Inevitable,” Commentary, 1956, p. 53.

[xliv] Jefferson School Oral History Project, September 2004, p. 61.

[xlv] Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 8, 1969.

[xlvi] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, July 12, 1962.

[xlvii] Ibid., July 1, 1963.

[xlviii] Conversation with Paul H. Cale Jr., February 2019. Paul Jr. participated in the sports programs at Albemarle High School during this time and vividly remembers his conversations with his father about the ban.

[xlix] Albemarle County Board of Supervisors Minutes, June 20, 1963.

[l] Letter written by Paul H. Cale Jr., February 27, 2019.

[li] Albemarle County School Board Minutes, June 10, 1968.

[lii] Letter written by A. L. Scott, July 25, 1975 [ATTACHED].

[liii] Development of Public Schools in Albemarle County from the Late 1700’s to 1976: A Bicentennial Project of the Retired Teachers Association of the County of Albemarle, Addendum, 1976.

[liv] Letter written by Suzanne Cale Wood (Paul Cale’s daughter), February 13, 2019.

[lv] The Daily Progress, October 16, 1968.

[lvi] Williamsburg Yorktown Daily, August 2, 2016.

[lvii] Ibid., April 20, 2016.

[lviii] The Virginia Gazette, March 29, 2016.

[lix] The Daily Progress, Obituary for Rosa Belle Moon Lee, December 6, 2013.

[lx] Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 1, 2016.

[lxi] Pratt, Robert A. The Color of Their Skin: Education and Race in Richmond, Virginia 1954-89, University Press of Virginia, p. 7.

[lxii] January 3, 2019 letter written by Curtis Tomlin to the editor of the Crozet Gazette.

[lxiii] August 1, 1983 letter written by Waldo E. Johnson to Paul and Hallie Cale on the occasion of their golden wedding anniversary.

Former students and teachers want Rawls Byrd Elementary renamed

by Ryan McKinnon THE VIRGINIA GAZETTE March 29,2016

WILLIAMSBURG — When Lafayette Jones, a black high school junior, asked to attend the all-white James Blair High School in 1960, his father got a phone call.

It was Rawls Byrd, the superintendent of Williamsburg-James City County Schools, making it clear that if Jones did not rescind his request, his father — a carpenter — would never find work in town again.

Byrd also paid a visit to the all-black faculty meeting at Bruton Heights School that day and told the staff that if Jones kept trying to attend James Blair, he would shut down Bruton Heights and fire all the teachers.

“He made a lot of threats, and I think he would have made good on them,” Jones said.

And, Jones said, as a result of Byrd’s attitude and behavior, Rawls Byrd Elementary School needs a new name.

Jones is organizing former students and teachers in an effort to persuade the current W-JCC School Board to change the name of the school. He said there were “quite a few” people involved in the movement, and roughly 10 people were coordinating a strategy to get the name changed.

Jones said the group will likely present their case during the public comment period at the School Board’s April 12 meeting.

“This has been a subject of discussion among blacks in the area for quite a while, but no one has taken action yet,” Jones said. “It’s something that I’ve wanted to do, and I’m not getting any younger.”

On March 10, the Henrico County School Board voted unanimously to change the name of Harry F. Byrd Middle School, which was named for the former state senator and governor whose leadership of the Massive Resistance movement stalled integration of schools.

Jones, who is now a 73-year-old retired Green Beret, said Henrico’s actions have encouraged him to take up the cause of getting the name changed.

“Today’s black kids should not be subjected to attending a school named after an individual who denied their parents and grandparents the opportunity for an education,” Jones said.

As historians have dug into the past, two different Rawls Byrds emerge.

The Rawls Byrd of public record was a man who helped shape Williamsburg-James City County Public Schools as they are known today.

In 1953, he oversaw the merger of the Williamsburg and James City County school systems, which was a controversial move at the time and one that many predicted would never work. He served as superintendent from 1928 to 1964.

Upon his retirement The Virginia Gazette painted a picture of his influence:

A July 10, 1964, editorial reads: “The story of Rawls Byrd is, in a very literal sense, the story of public schools in Williamsburg and James City County. … it seems a shame he must retire.”

Yet a different Rawls Byrd emerges for the black students and teachers who learned and worked under him.

Vivian Bland, 82, remembers meeting the superintendent as part of a government class project. The students had the chance to ask Byrd questions, so Bland asked him why Bruton Heights did not have any foreign language classes.

“Mr. (Rawls) Byrd’s answer to me was, ‘You learn to speak English correctly and maybe you can have a foreign language,’ ” Bland said.

Bland also said she remembers Rawls Byrd refusing to shake the hands of black students graduating from Bruton Heights.

“It may seem like small gestures, but it was just consistently trying to demean and not give a person their due justice,” she said. “He made it known how he felt about us.”

Brady Graham, 83, began teaching at Bruton Heights in 1959. He said he feared integration because of a speech Rawls Byrd made at a PTA meeting.

“I still remember Mr. Byrd coming to a PTA meeting at Bruton Heights and saying to the audience that he could visualize white teachers teaching blacks, but he could not visualize black teachers teaching whites,” Graham said. “That was the assumption — that if they integrated, all the black teachers would be fired.”

Graham also remembered Rawls Byrd’s threats the day Jones applied for a transfer to James Blair. And he repeated a claim many from the era have made about Byrd, that he said he would retire before he would oversee an integrated school system.

A June 5, 1964, Virginia Gazette story reported that 10 years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against segregation, five black students had applied for admission into Matthew Whaley Elementary School and James Blair High School.

On June 23 of the same year, School Board chairman John E. Wray stepped down in protest over the integration. Rawls Byrd announced his retirement on July 7.

While Byrd’s attitude toward race relations is not as documented as staunch segregationists such as Harry F. Byrd, historian Jodi Allen said the oral history of people who interacted with him should not be discounted.

Allen is a visiting assistant professor of history at the College of William and Mary, and the managing director of the Lemon Project — a project aimed at rectifying the college’s oppression of blacks throughout slavery and Jim Crow eras.

Researchers for the Lemon Project interviewed several students and teachers who attended W-JCC schools during the segregation era, and Allen said the same picture keeps emerging.

“You can’t trust any source in and of itself. They all have to be supported with evidence,” Allen said. “The fact that everyone talks about him in the same way, I think we can say he had segregationist leanings.”

Current School Board Vice Chairwoman Kyra Cook said she is not surprised to hear there is interest in getting the name changed, but she declined to comment on whether she thinks it is necessary. She said she has studied the issue as other localities have dealt with similar situations.

Cook said if name-change activists make compelling arguments during the public comment period at School Board meetings, the board could ask the superintendent’s office to look into it and make a recommendation for the board to vote on.

One of the factors in changing the name is the cost of rebranding. In Henrico, school officials estimate it will spend roughly $13,000 in replacing a sign, scoreboard signage, rug and stationery, all emblazoned with “Byrd.”

W-JCC spokeswoman Betsy Overkamp-Smith said the district has not looked into the cost of a name change because the issue has not been formally brought to the board for discussion.

Former School Board member Joe Fuentes said he heard rumblings about the name at different points during his 10-year tenure, but there was never a clear effort to get it changed.

“I was always wondering if that was going to happen,” he said. “I knew that day is going to come and someone is going to say, ‘You really need to change that.’ ”

WILLIAMSBURG- In a 6 to nothing vote, the Williamsburg-James City County School Board voted to “begin the process” of changing the name of Rawls Byrd Elementary School on Tuesday night.

– Ryan McKinnon, THE VIRGINIA GAZETTE, May 26, 2016

To the Crozet Gazette Editor: Paul Cale, Sr.

January 3, 2019

I am a subscriber to your paper and read it cover to cover each month in an attempt to keep abreast of the events and people of my hometown. I was born in Crozet in 1933 and lived there happily, only moving away in 1971 for an employment opportunity elsewhere. When my wife and I married, we looked for and found the location and home in which we hoped to raise our family, in Wayland Park, Crozet. Our prior home is easy to find as it is the only home in the original Wayland Park facing east, directly across from the home of Mr. and Mrs. Ben Hurt.

We were blessed to live in Wayland Park from July 1957 to February 1971. We brought our son and daughter to that home in 1957 and 1959 respectively; moving away was not an easy decision. Each of us has made what we term “pilgrimages” back to Crozet as our time and fortunes permitted. My wife and I relocated in 1980 to the Clearwater, Florida area, where I still reside. My wife, the former Peggy Sandridge, passed away here in 2014.

This background is by way of leading to the fact that I have been acquainted on a very personal level with Mr. and Mrs. Paul Cale, Sr., and their children, from my very early memoires until the passing of Mr. and Mrs. Cale; I am still in occasional contact with their son, Paul Jr. I submit that I knew Mr. Cale, Sr., as a friend for many years and more closely as a neighbor, too, from 1957 to 1971.

In the late 60s, I was among a group who sought to revive Crozet Park when it had seemed to lose its way. As a group, we agreed to seek community-wide support and funding, and each of us took a group of names to contact for that purpose. One of the names I selected, on purpose, was that of Mr. Paul H. Cale. I called for an appointment and was graciously invited into his home on St. George Ave. I explained my purpose and both he and Mrs. Cale immediately jumped on the bandwagon. Mr. Cale brought out his checkbook and while writing a check, he asked me if we intended to keep the park open to everyone, including the black community. My reply, simply, was “We had not thought not to!” He smiled, thanked me and said, “That’s what I wanted to hear.”

That’s the man that some reporter, who failed to do his homework, and the man that the chairperson of the Albemarle County School Board, Dr. Kate Acuff—taking that reporter’s work as the truth—vilified publicly as a racist. How absurd! While this is shocking, I am further appalled that our local news people have not taken up arms, done the required study as a good reporter does, and called these people to task for the denigration of the finest man, not to mention, educator, Albemarle County has ever known!

—Curtis Tomlin, Palm Harbor, Florida

Waldo Johnson Letter to Paul and Hallie Cale

August 1, 1983

My hat is off to you, Reverend Thomas, for all the work you’ve put into this. I can’t come to an opinion on the issue, having not read a response to what you’ve written. But you very much deserve a response, and if one is not forthcoming, that speaks for itself.

I’m going to respond to this post for a few reasons. First because I am a parent of a child of color in Albemarle county schools, second because I attended schools in Albemarle county as a child (as did my father before me), and third because I was raised by Dr. Jim Bash, a local civil rights educator who also knew Paul Cale and who did the real work of desegregating and teaching integration in local public schools and many many other public schools across the south.

I’m confused about the anger over the re-naming of the school. Originally when Cale and for that matter the other area schools (Stone-Robinson, Agnor-Hurt etc, were named, there was a debate about why they were named after people at all. This argument over naming is older than most people know. The concern was raised at the time (by my grandfather and others, that there would never be any named after black educators (or other minority groups) because at the time no people of color were in positions of power. As my grandfather was aware and his contemporaries (Nathan Johnson, Bob Anderson, Hank Allen et al.), the level of education and career advancement available to people of color was prohibitive at that time. In essence there was a system of structural racism that prevented advancement of people of color and therefor none would have been in a position to be upheld as a leader to the same extent as their white counterparts. Opponents to honorary school naming considered its repercussions at the time to be detrimental to the community in the same way as it now manifests–contentious debate over whom is deserving of accolades and in what ways they should be honored. Paul Cale may have been a good principal–that isn’t the argument. What is a problem is that few other persons of color from his time would have had the same recognition. My grandfather and others felt that schools as paradigms of public freedoms and opportunity–as citizenship builders, as representations of the possibility to all that the American Dream is not a fantasy should never be housed in a building bearing the name of any one individual, ethnic group or representation of a pre-determined ideal. Rather numbers such as those assigned to schools in large cities or names indicating geographic locations would be a more reasonable and appropriate nomenclature and avoid exactly the debate we are experiencing today.

Further, as the parent of a child of color I find it curious that so much detail is being lent to the name of a school while many many children of color are suffering under disparate impact policies and administrative decisions that exclude children of color from free and appropriate public education. The purpose of public school is to “educate students as effective and transformative citizens of the commonwealth”(Banks 2006). Equity pedagogy is not just the renaming of buildings, it is not just lip-service for the public while behind the scenes educators working with children continue to implement and act on institutional and structural biases. Teachers must be tasked with deep inter and intra-group understanding along with the flexibility to toggle between group and individual learning style and interactions. Unfortunately this is not the case in most classrooms in the county at the moment. Children who witness and experience the effects of un-acknowledged structural and individual prejudices are instead deemed problem kids. “When targets of micro-agressions attempt to point out the offensive nature of remarks and actions from perpetrators, they are told that their perceptions are inaccurate, that they are oversensitive, or that they are paranoid (Sue 2010).

Have we gone back in time to believe the crude caricatures of racial divisions created by those white ‘scientists’ who published in The Racial History of Man in 1922 or the atrocity of the The Birth of a Nation–declaring that all skin colors other than white were less intelligent, less able, less inspiring? I recall as a child being in the middle of these debate (sadly it still exists today). The only local heroes we have are those with white faces. The reason is as I stated above but also because we have been trained to see ideal characteristics as those of past leaders. As stated previously, those were seldom other than white. When I attended the Dialogue on Race in 2009 I recal a (white) gentleman stating that he followed the ideal that he would respect those who respected themselves. In his mind this meant wearing what he deemed appropriate clothing and behaving in a way that seemed respectable to him. I asked him who determined what clothes and manners were appropriate? I ask the same question today–why do we hold Mr. Cale as the paradigm of virtue and not another? Again, this is not a criticism of he, but rather of ourselves. Look within to examine why he was chosen and who made that decision. As my grandfather said at the time–it is based on an unfair advantage which few people of color could ever achieve within the structure as it was/is.

Sadly I fear the same is true today. With my son and many other of his non-white peers, the same impediments to learning and achievement remain in place. Thus they ability to become fully functional, community engaged, participatory citizens is compromised. Children of color are less likely to be provided with learning accommodations, less likely to go on to four year colleges, less likely to be in advanced classes. Conversely, they are more likely to be identified as behavioral problems, sent to detention, suspended, drop out, end up incarcerated. Case in point, my own son has been denied evaluation and accommodations for a his disability, has spent more than 52 occasions in detention in the last school year and continues to struggle with problems with receiving appropriate education from Albemarle County Schools.

The irony of the Albemarle County superintendent’s desire to remove Mr. Cale’s name from the school while simultaneously ignoring the dilemma of many children of color who spend hours and even days imprisoned within a detention room rather than receiving education to become fully engaged citizens is not lost on me or many other concerned citizens. My hope is that we will not be sucked into the minutia of the name debate while ignoring this school-to-prison pipeline which exists just under the veneer surface of these public displays of seeming racial and cultural sensitivity. Yes I would like to see the names changed to avoid the continued use of mono-cultural ideals as representatives of virtue. But I do not wish it to come at the expense of real in-practice instructional biases enacted upon our next generation of local citizens.

I understand the fear in addressing the structural racism present within our schools–“People who rely on the current system are afraid to dismantle it…saying this is just the way things are, we have to make the best of it” (Villanueva 2018).

But this racism from within affects each of us deeply as individuals and collectively our community is impacted in hugely negative ways. When we are unable to produce a next generation of fully educated and contributory citizens, we lose out on the wealth that is generated by their businesses, services and industry. “…with such a large and mixed population of people who fall into this category their economic impact through financial transactions should not be ignored” (Rojas 2010).

My challenge to each of us and specifically to Albemarle County Schools is to not be side-tracked from the real work necessary to clean out the fetid internal structure lying just under the surface. Yes change the name if you are able. Keep our eyes open to the reasons those names were chosen in the first place (regardless of the individual attributes or not of those namesakes); but this work should be a sideline to the much more important and meaningful work that our community desperately needs–clean up the internal structures, decision-making process and individuals acting on and through personal and institutional racist paradigms. There are identifiable components of our schools that have been well documented and which disproportionately and negatively impact non-white and immigrant children which include “a tendancy towards measuring everything in relation to ideological goals, (and) disregarding human and aesthetic values in the process” (Cerroni-Long 2002).

References:

Banks, James A. Educating Citizens in a Multicultural Society, 2nd Edition. Teachers College, Columbia University. 2007

Cerroni-Long, E.L. “Life and Cultures: The Test of Real Participant Observation” in Distant Mirrors, America as a Foreign Culture, 3rd Edition. Wadsworth Group, Canada. 2002

Rojas, Daisy, “Accessing Alternatives; Latino Immigrant Financial Services in Virginia”. International Journal Of Business Anthropology. 2010

Sue, Derald Wing, Microagressions and Marginality; Manifestation, Dynamics and Impact. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken 2010

Villanueva, Edgar, Decolonizing Wealth; Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance. Oakland 2018

Mrs Rojas, you continually speak of the current racism present in the school system yet you offer not one specific example. Making such vague serious divisive charges is reckless. I’m not disagreeing with you but when I make such flammable comments I try to be sure and explicitly give examples to explain my reasoning. Please list the current roadblocks you speak of. There is an expression in the corporate world I worked in for almost 40 years. “Never complain about the status quo you work in unless you have specific examples and hopefully possible solutions.” It’s one of the few wise corporate expressions we were forced to at least pretend to support over the years.